When I was a young coder, just starting out in the big scary world of enterprise software, an older, far more experienced chap gave me a stern warning about hard coding values in my software. “They will have to change at some point, and you don’t want to recompile and redeploy your application just to change the VAT tax rate.” I took this advice to heart and soon every value that my application needed was loaded from a huge .ini file. I still think it’s good advice, but be warned, like most things in software, it’s good advice up to a point. Beyond that point lies pain.

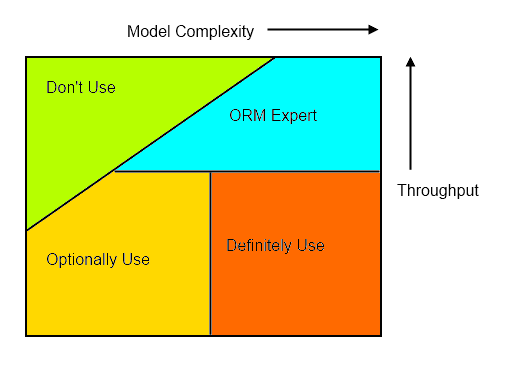

Let me introduce you to my ‘Configuration Complexity Clock’.

This clock tells a story. We start at midnight, 12 o’clock, with a simple new requirement which we quickly code up as a little application. It’s not expected to last very long, just a stop-gap in some larger strategic scheme, so we’ve hard-coded all the application’s values. Months pass, the application becomes widely used, but there’s a problem, some of the business values change, so we find ourselves rebuilding and re-deploying it just to change a few numbers. This is obviously wrong. The solution is simple, we’ll move those values out into a configuration file, maybe some appsettings in our App.config. Now we’re at 2 on the clock.

Time passes and our application is now somewhat entrenched in our organisation. The business continues to evolve and as it does, more values are moved to our configuration file. Now appsettings are no longer sufficient, we have groups of values and hierarchies of values. If we’re good, by now we will have moved our configuration into a dedicated XML schema that gets de-serialized into a configuration model. If we’re not so good we might have shoe-horned repeated and multi-dimensional values into some strange tilda and pipe separated strings. Now we’re at 4 or 5 on the clock.

More time passes, the irritating ‘chief software architect’ has been sacked and our little application is now core to our organisation. The business rules become more complex and so does our configuration. In fact there’s now a considerable learning curve before a new hire can successfully carry out a deployment. One of our new hires is a very clever chap, he’s seen this situation before. “What we need is a business rules engine” he declares. Now this looks promising. The configuration moves from its XML file into a database and has its own specialised GUI. Initially there was hope that non-technical business users would be able to use the GUI to configure the application, but that turned out to be a false hope; the mapping of business rules into the engine requires a level of expertise that only some members of the development team possess. We’re now at 6 on the clock.

Frustratingly there are still some business requirements that can’t be configured using the new rules engine. Some logical conditions simply aren’t configurable using its GUI, and so the application has to be re-coded and re-deployed for some scenarios. Help is at hand, someone on the team reads Ayende’s DSLs book. Yes, a DSL will allow us to write arbitrarily complex rules and solve all our problems. The team stops work for several months to implement the DSL. It’s a considerable technical accomplishment when it’s completed and everyone takes a well earned break. Surely this will mean the end of arbitrary hard-coded business logic? It’s now 9am on the clock.

Amazingly it works. Several months go by without any changes being needed in the core application. The team spend most of their time writing code in the new DSL. After some embarrassing episodes, they now go through a complete release cycle before deploying any new DSL code. The DSL text files are version controlled and each release goes through regression testing before being deployed. Debugging the DSL code is difficult, there’s little tooling support, they simply don’t have the resources to build an IDE or a ReSharper for their new little language. As the DSL code gets more complex they also start to miss being able to write object-oriented software. Some of the team have started to work on a unit testing framework in their spare time.

In the pub after work someone quips, “we’re back where we started four years ago, hard coding everything, except now in a much crappier language.”

They’ve gone around the clock and are back at 12.

Why tell this story? To be honest, I’ve never seen an organisation go all the way around the clock, but I’ve seen plenty that have got to 5, 6, or 7 and feel considerable pain. My point is this:

At a certain level of complexity, hard-coding a solution may be the least evil option.

You already have a general purpose programming language, before you go down the route of building a business rules engine or a DSL, or even if your configuration passes a certain level of complexity, consider that with a slicker build-test-deploy cycle, it might be far simpler just to hard code it.

As you go clockwise around the clock, the technical implementation becomes successively more complex. Building a good rules engine is hard, writing a DSL is harder still. Each extra hour you travel clockwise will lead to more complex software with more bugs and a harder learning curve for any new hires. The more complex the configuration, the more control and testing it will need before deployment. Soon enough you’ll find that there’s little difference in the length of time it takes between changing a line of code and changing a line of configuration. Rather than a commonly available skill, such as coding C#, you find that your organisation relies on a very rare skill: understanding your rules engine or DSL.

I’m not saying that it’s never appropriate to implement complex configuration, a rules-engine or a DSL, Indeed I would jump at the chance of building a DSL given the right requirements, but I am saying that you should understand the implications and recognise where you are on the clock before you go down that route.